It then presents evidence regarding the adverse effects on workers who work such irregular and on-call work schedules, in contrast to those with more regular shift times. The outcomes of interest are work-family conflict and work stress. It will also present evidence of the beneficial effects on work-family integration and work stress when employees report having input into the scheduling of their work and/or flexible work schedules. In Congress, the Schedules that Work Act of 2014 (H.R. 5159), would extend this still further in scope. This new right would target four key industries where irregular scheduling has been concentrated.

It would require a minimum of 14 days advance notice for posting schedules. It also would mandate a minimum reporting payment for call-off and one hour's pay for split-shifting practices. Specifically, the bill would require employers to inform workers in writing of their expected minimum hours and job schedule, on or before their first day of work.

If the schedule and minimum hours happen to change, the employer would be required to notify the employee at least two weeks before the new schedule comes into effect. Employers would begin to have to compensate workers when they are sent home from work earlier than planned, paid at their regular rate for four hours or the total length of the workers' shift if the shift is less than four hours. Advance notice of schedules is distributed quite differently among occupational groups. Among service workers, production workers, and skilled trades, most employees know their schedule only one week or less in advance. Service and production supervisors, however, are among both those with the shortest and the longest advance notice categories. In contrast, the majority of professionals, business staff, and providers of social services know their work schedule four or more weeks in advance.

Furthermore, approximately 74 percent of employees in both hourly and nonhourly jobs experience at least some fluctuation in weekly hours over the course of a month. Among workers with children, 40 percent report one week or less advance notice and 50 percent say they have no input into their schedule. Employers determine the work schedules of about half of young adults without employee input, which results in part-time schedules that fluctuate between 17 and 28 hours per week. For the majority of employees who work fewer than 40, as well as those with more than 44 hours in a normal week, hour fluctuation is the norm.

So, among workers with the longest hours, the 40-hour workweek seems not to be the norm but rather, just a lower bound. The mean variation in the length of the workweek is 10 hours among hourly workers as compared with nearly 12 hours among nonhourly workers. Among the 74 percent of hourly workers who report having fluctuations in the last month, hours vary by a whopping 50 percent of their usual work hours, on average.

One key source of underemployment is that at least periodically, employees are scheduled for fewer hours than they prefer to be working, in days or weeks that are not necessarily regular or predictable. Thus, the consequent experience of involuntary part-time employment not only constrains the incomes of those workers, but often makes the daily work lives of those individuals unpredictable and more stressful. Interestingly, there is also a nontrivial proportion of workers who actually would prefer to work fewer hours even if it means proportionally less income. Sixth, to protect against overwork, employers must secure employees' consent to work with less than 11 hours rest between work shifts and employees must be compensated at a time-and-a-half pay rate if the employee agrees to work such hours. This right is targeted to those who arguably need or value it the most—it must be granted unequivocally if the request is due to a serious health condition, caregiving obligations, educational pursuits, or requirements of a second job.

Ninth, employers must offer hours to existing (not just part-time) employees before hiring new staff or temporary workers. Finally, protection against retaliation is stronger, placing the burden on employers to show that an adverse action against an employee who exercised his or her rights or assisted others to assert their rights, was not retaliatory in nature. Enforcement would include an individual right to pursue civil penalties, in addition to actions by an office of labor standards. In 2014, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved new protections for the city's retail workers, which took effect on January 5, 2015.

The measures are intended to give hourly retail staffers more predictable schedules and priority access to extra hours of work available. The legislation applies to retail chains with 20 or more locations nationally or worldwide and that have at least 20 employees in San Francisco under one management system (thus affecting about 5 percent of the city's workforce). The ordinances require businesses to post workers' schedules at least two weeks in advance. Workers will receive compensation for last-minute schedule changes, "on-call" hours, and instances in which they are sent home before completing their assigned shifts.

More specifically, workers will receive one hour of pay at their regular rate of pay for schedule changes made with less than a week's notice and two to four hours of pay for schedule changes made with less than 24 hours' notice. Finally, it prohibits formula retail employers from discriminating against employees with respect to their rate of pay, access to employer-provided paid and unpaid time off, or access to promotion opportunities. This will more forcefully protect employees on part-time status, for example, by providing part-timers and full-timers equal access to scheduling and time-off requests. The fact that household income has become more volatile in the most recent four decades, through the late 2000s, is a key labor market development.

It is also surprising, given the relatively higher stability in the macroeconomy until 2007. A surprisingly high share of Americans report experiencing significant spikes and dips in their incomes. Most important here, among such workers, 42 percent attribute the variability to an irregular work schedule . This reason for income volatility, an , constitutes almost as much as all other work reasons put together. Of the 42 percent whose work hours change from week to week, 58 percent work full-time, 30 percent work part-time, and 11 percent are self-employed. Tellingly, over 3 in 4 workers stated a preference simply for financial stability, over "moving up" .

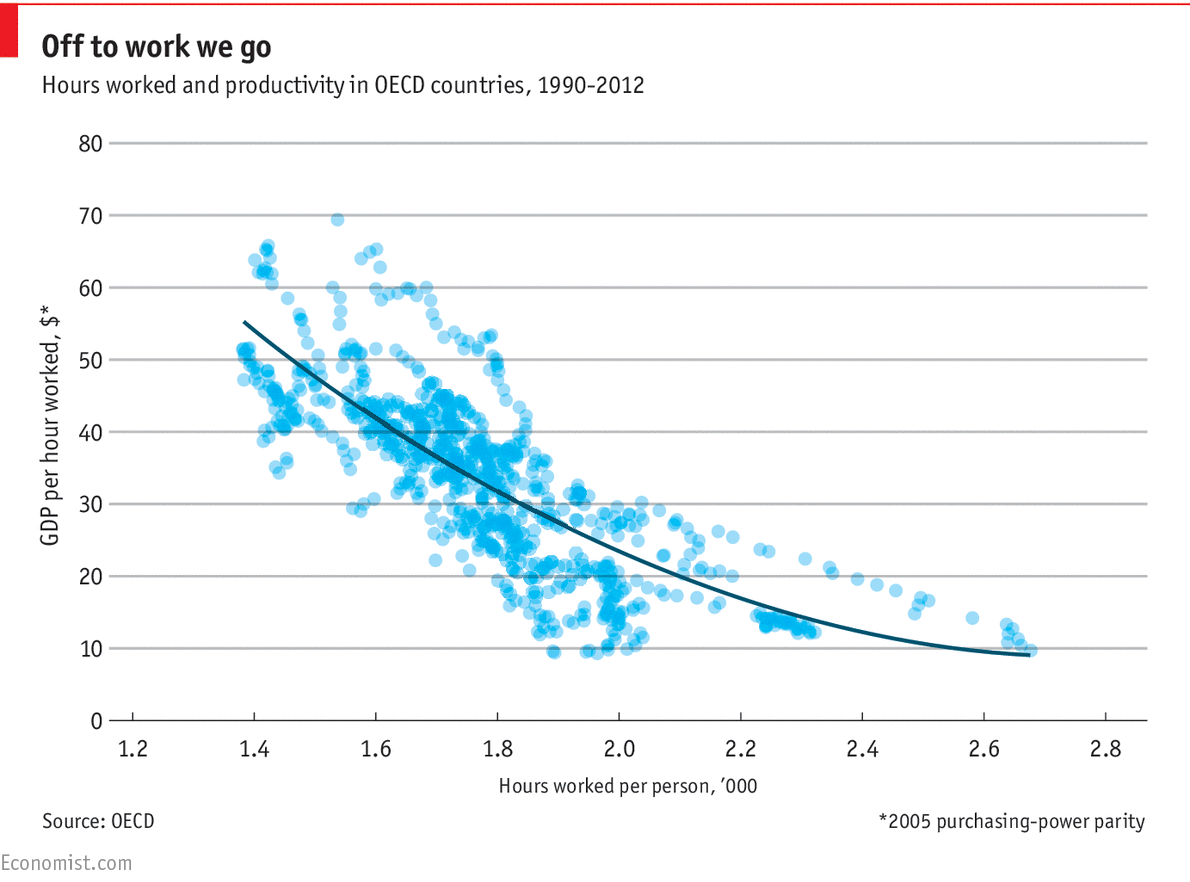

Historically employers and employees often agreed on very long workweeks because the economy was not very productive (by today's standards) and people had to work long hours to earn enough money to feed, clothe and house their families. The long-term decline in the length of the workweek, in this view, has primarily been due to increased economic productivity, which has yielded higher wages for workers. Workers responded to this rise in potential income by "buying" more leisure time, as well as by buying more goods and services. In a recent survey, a sizeable majority of economic historians agreed with this view.

Over eighty percent accepted the proposition that "the reduction in the length of the workweek in American manufacturing before the Great Depression was primarily due to economic growth and the increased wages it brought" . For example, roughly two-thirds of economic historians surveyed rejected the proposition that the efforts of labor unions were the primary cause of the drop in work hours before the Great Depression. As the length of the workweek gradually declined, political agitation for shorter hours seems to have waned for the next two decades.

However, immediately after the Civil War reductions in the length of the workweek reemerged as an important issue for organized labor. Roediger argues that many of the new ideas about shorter hours grew out of the abolitionists' critique of slavery — that long hours, like slavery, stunted aggregate demand in the economy. The hub of the newly launched movement was Boston and Grand Eight Hours Leagues sprang up around the country in 1865 and 1866.

The leaders of the movement called the meeting of the first national organization to unite workers of different trades, the National Labor Union, which met in Baltimore in 1867. The passage of the state laws did foment action by workers — especially in Chicago where parades, a general strike, rioting and martial law ensued. In only a few places did work hours fall after the passage of these laws. Many become disillusioned with the idea of using the government to promote shorter hours and by the late 1860s, efforts to push for a universal eight-hour day had been put on the back burner.

Some employers have undertaken fair scheduling initiatives on their own. Some companies have instructed their local store managers to consider requests for making schedules more stable or consistent week to week, such as Starbucks and Ikea, which provides up to three weeks' advance notice of upcoming schedules. Such workers are also empowered to engage in the key practice of shift-swapping.

President Obama has directed the federal Office of Personal Management to initiate more flexible work and workplace options for the approximately 2 million federal employees. The agencies must facilitate conversations about work schedule flexibilities, including telework, part-time employment, or job sharing arrangements. Supervisors have to confer directly with the requesting employee as appropriate to understand fully the nature and need for the requested flexibility, and carefully respond within 20 business days of the initial request. In addition, other sections provide part-time and job sharing, telework, break times, and private spaces for nursing mothers. Canada has legislated reporting pay requirements in its federal sector and in several of its provinces. In Ontario, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Alberta, compensation is mandated for a minimum of three hours at the minimum wage.

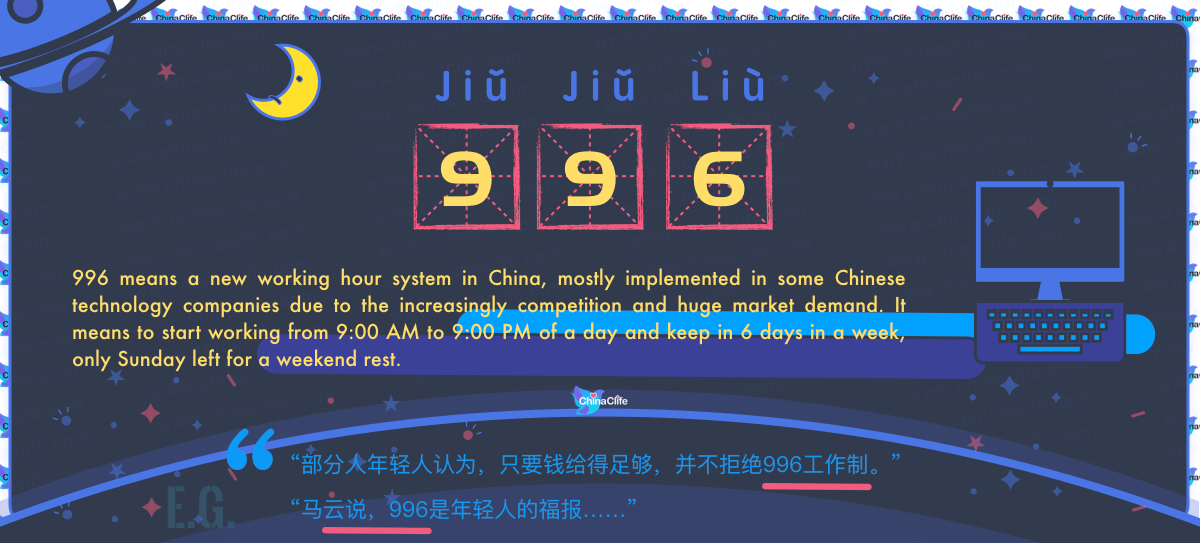

In Quebec, Prince Edward Island, and Manitoba, compensation is mandatory at a minimum of three hours at the employee's regular wage. In the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, employees are owed four hours at the regular wage if they show up to work their shift and less than four hours of work is provided. Finally, employees have the right to refuse overtime without repercussions in Saskatchewan, Québec, and Yukon. Some full-time employees also choose to work 55 hours per week. Working 55 hours per week, which is more hours than average for full-time workers, is considered a heavy workload. This schedule may be common for trade workers, medical professionals and other occupations.

If you work 55-hour weeks, it's important to make time to take care of yourself. Try to to make time for exercise, eat a healthy diet and manage your stress. It's also important to stay organised so you can maintain a healthy work-life balance.

First, the Minnesota bill would apply to all employees , not just in the retail sector. Second, the amount of advance notice would be three weeks, not just two, for employers to post employees' initial schedules, including on-call shifts, and employees must be notified of schedule changes at least 24 hours prior to the change. Third, employers must get consent from workers in order to add hours or shifts after the initial schedule is posted. Fifth, employees would be entitled to receive reporting pay of four hours or the duration of the shift, whichever is less, when their employer cancels or shortens a shift with less than 24 hours' notice. A sampling of retail sector workers in and around New York City finds that only 40 percent of such employees have a minimum number of hours set per week . Moreover, a quarter of them work "on-call" shifts, with most not finding out if they are needed at work until two hours before the start of the shift.

The labor market continues to recover, but a stubbornly high rate of underemployment persists as more than five million Americans are working part-time for economic reasons (U.S. BLS 2015a; 2015b). Not only are many of this type of underemployed worker, by definition, scheduled for fewer hours, days, or weeks than they prefer to be working, the daily timing of their work schedules can often be irregular or unpredictable. This both constrains consumer spending and complicates the daily work lives of such workers, particularly those navigating through nonwork responsibilities such as caregiving.

This variability of work hours contributes to income instability and thus, adversely affects not only household consumption but general macroeconomic performance. Labor markets became very tight during World War I as the demand for workers soared and the unemployment rate plunged. These forces put workers in a strong bargaining position, which they used to obtain shorter work schedules. The move to shorter hours was also pushed by the federal government, which gave unprecedented support to unionization. The federal government began to intervene in labor disputes for the first time, and the National War Labor Board "almost invariably awarded the basic eight-hour day when the question of hours was at issue" in labor disputes .

At the end of the war everyone wondered if organized labor would maintain its newfound power and the crucial test case was the steel industry. These abnormally long hours were the subject of much denunciation and a major issue in a strike that began in September 1919. The strike failed (and organized labor's power receded during the 1920s), but four years later US Steel reduced its workday from twelve to eight hours. The move came after much arm-twisting by President Harding but its timing may be explained by immigration restrictions and the loss of immigrant workers who were willing to accept such long hours .

The movement for shorter hours as a depression-fighting work-sharing measure built such a seemingly irresistible momentum that by 1933 observers predicting that the "30-hour week was within a month of becoming federal law" . Hunnicutt argues that an implicit deal was struck in the NIRA. Labor leaders were persuaded by NIRA Section 7a's provisions — which guaranteed union organization and collective bargaining — to support the NIRA rather than the Black-Connery Thirty-Hour Bill.

Business, with the threat of thirty hours hanging over its head, fell raggedly into line. Despite a plan by NRA Administrator Hugh Johnson to make blanket provisions for a thirty-five hour workweek in all industry codes, by late August 1933, the momentum toward the thirty-hour week had dissipated. About half of employees covered by NRA codes had their hours set at forty per week and nearly 40 percent had workweeks longer than forty hours. Many employees are curious about how many hours they can work in a week. Part-time employees usually work fewer than 38 hours per week. The part-time hours you work may depend on factors such as your contract or any paid overtime you agree to.

You might also make an agreement with your employer regarding the number of hours you'll work. Alternatively, full-time workers typically work 38 hours per week or more, and often, five days a week. Some industries such as manufacturing or medical often require full-time employees to work more than 38 hours per week. Processes to improve the quality of part-time work include granting part-time workers pro-rata earnings and benefits, and rights to request changes in their working hours.

It includes "reversibility"—to be able to move back from part-time to full-time hours after having moved from full-time to part-time. Not only the duration of working hours, but also work schedule predictability can be addressed through legislation. Fostered a move on the part of the British government (termed, "BIS ") in June 2014 to ban the use of exclusivity clauses in such contracts. Eastern European immigrants worked significantly longer than others, as did people in industries whose output varied considerably from season to season.

High unionization and strike levels reduced hours to a small degree. The average female employee worked about six and a half fewer hours per week in 1919 than did the average male employee. In city-level comparisons, state maximum hours laws appear to have had little affect on average work hours, once the influences of other factors have been taken into account.

One possibility is that these laws were passed only after economic forces lowered the length of the workweek. Overall, in cities where wages were one percent higher, hours were about -0.13 to -0.05 percent lower. Again, this suggests that during the era of declining hours, workers were willing to use higher wages to "buy" shorter hours. The length of the workweek, like other labor market outcomes, is determined by the interaction of the supply and demand for labor. On the other hand, longer hours can bring reduced productivity due to worker fatigue and can bring worker demands for higher hourly wages to compensate for putting in long hours.

If they set the workweek too high, workers may quit and few workers will be willing to work for them at a competitive wage rate. Thus, workers implicitly choose among a variety of jobs — some offering shorter hours and lower earnings, others offering longer hours and higher earnings. A new cadre of social scientists began to offer evidence that long hours produced health-threatening, productivity-reducing fatigue.

This line of reasoning, advanced in the court brief of Louis Brandeis and Josephine Goldmark, was crucial in the Supreme Court's decision to support state regulation of women's hours in Muller vs. Oregon. In addition, data relating to hours and output among British and American war workers during World War I helped convince some that long hours could be counterproductive. Businessmen, however, frequently attacked the shorter hours movement as merely a ploy to raise wages, since workers were generally willing to work overtime at higher wage rates. Last month Alda, an Icelandic pressure group, and Autonomy, a British think-tank, published a report into experiments by the Reykjavik City Council and Iceland's government between 2015 and 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.